Houses of the Holy - The Temple in Anglo-Saxon England

What defined the ritual landscape of the Temple?

At Ithavoll met | the mighty gods,

Shrines and temples | they timbered high;

Forges they set, and | they smithied ore,

Tongs they wrought, | and tools they fashioned.

— Völuspá 7, Elder Edda

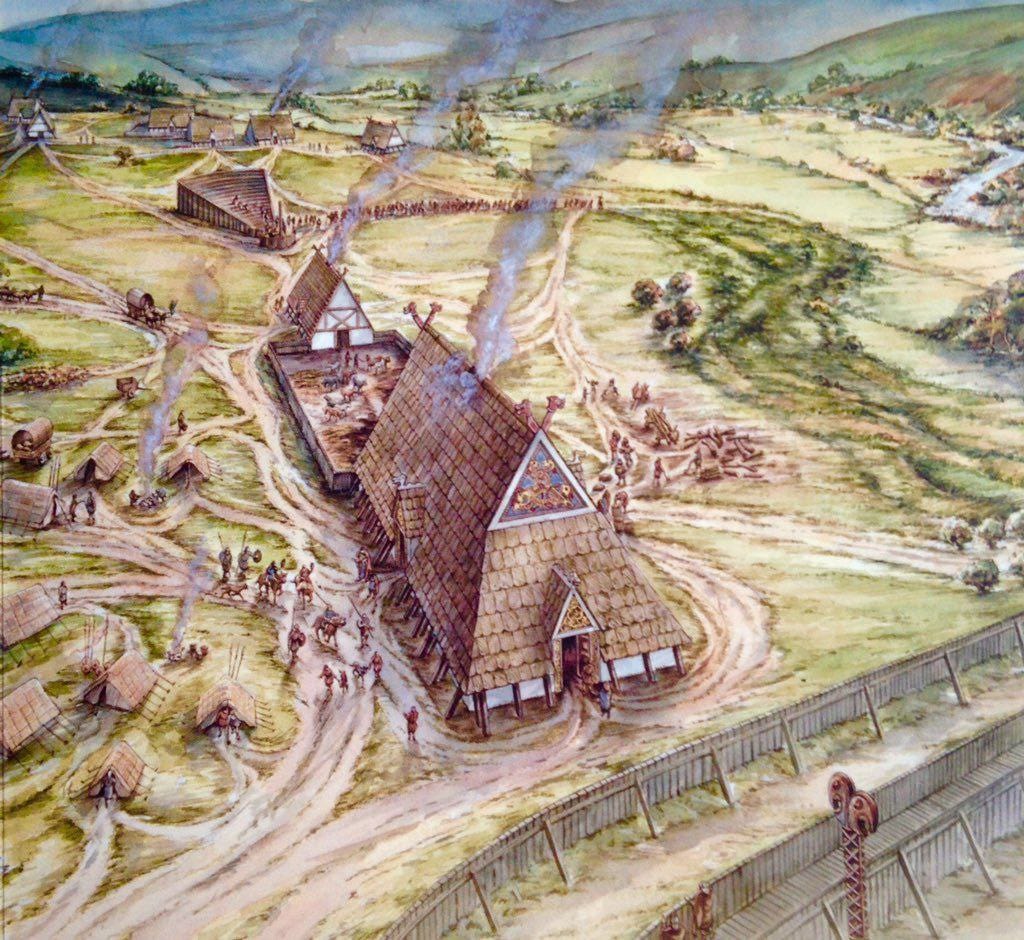

The Anglo-Saxon Temple has remained an enigmatic structure from the height of its use during the time of our ancestors to even now. Especially as we recover the faith of the English from centuries of obfuscation. However, since the publishing of Brian Hope-Taylor’s seminal work on the site at Yeavering. The library of knowledge surrounding the Anglo-Saxon Temple has only grown in size.

Henceforth, the aim of this work is to coalesce many of the existing sources for the Anglo-Saxon Temple into a document which defines the Temple building, its cycle of usage and the implications of these findings for the construction of new Temples today.

I. Houses of the Holy

It is evident that there is a loose criteria that can define what makes an Anglo-Saxon Temple. Of the very few examples that have been identified and dug by Archaeologists, or simply only known of through literary records. The characteristics of being located on raised ground, a proximity to water, ritual disposition of animal bones and evidence of standing posts connected with the Temple building.

This criterion demonstrates commonalities of ritual structures across early Anglo-Saxon England that shows a general convention for building ritual complexes. Although this convention appears to be applied to various degrees with each Temple site. It is this convention that can be a framework for the establishment of new Temples for those who follow the faith of our ancestors.

The location of Temple structures on raised spurs of land or hilltops at face value is evidential of these buildings placed above and apart from the regular dwellings of the people worshipping in them. Certainly, the Temple building D2 at Yeavering, the site of the Temple at Goodmanham and Harrow-on-the-Hill in Greater London are each prominent examples of this being the case.1 However, this can be applied to varying degrees depending on the location in question. A prime example of this is evident in the site at Sutton Courtenay/Drayton in Oxfordshire which sits on only the slightest of rises in the surrounding landscape.2 Evidentially this commonality can be seen across each of these sites to varying degrees as the landscape changes in accordance with locations on which our ancestors had to build a Temple.

Theoretically, the locating of Temples on top of raised ground may also be viewed in the context of raising the place of worship up to the heavens, in the sense of being closer to the Gods.3 However, there is no evidence to suggest that there were efforts to build spire-like structures or places of worship increasing in height as is evidential in other cultures.4 Hence, the placing of Temple buildings on raised ground is more likely due to an effort to mark these places of worship as special.

Further reinforcing this, those Temple sites that have been subject to Archaeological investigation have shown these buildings as surrounded by a border fence.5 Further delineating the space on which the Temple sits as sacred and other to the land around it. In the same way as the placing of the Temple on high ground marks its other status among a wider hierarchy of structures.6

Depicted: the entrance to the remains of the Temple at Yeavering; date unknown.

Another possible method by which these Temple Buildings were marked out from the buildings around them can be seen in a form of ritualistic alignment towards the movement of heavenly bodies. Evident in the Temple D2 at Yeavering and the site at Goodmanham, it is uncertain if this is the case in other examples of Temples in Anglo-Saxon England.7 As of all the construction conventions that appear to a degree.

This proves to be the least clear. Due to the very minimal amount of investigation and excavation that has been done into the Temple sites known of. It is exceedingly difficult to apply some form of ritualistic alignment as a commonality across the board. However, concerning the sites of Yeavering and Goodmanham it is apparent.8 Although, it is probable that these alignments have only come to light as a consequence of these sites receiving considerably more invested into their research when compared with other such Temple sites.

If further investigation were to delve into the sites at Foxley in Wiltshire, or Cowdery’s Down and Charlton both in Hampshire.9 Then it may be possible to discern if purposeful alignment of the Temple building was a commonality held across Anglo-Saxon England or something only apparent in certain instances. However, the proximity of Temple buildings to bodies of water is a consistent factor. Although not always flowing rivers or streams. The consistency with which Temple buildings are located in proximity to springs, pools, or wetlands marks both the buildings and the land itself as locations of significance.

Taking the known examples of ritual deposition of items into bodies of water and wetland.10 The placing of ritual buildings close to pre-existing sites of observance is recognisable as a key element for the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxons in their construction of Temple buildings. Notably, the most evident case in which this appears is also the case of the most thoroughly Archaeologically investigated of Anglo-Saxon Temple sites at Yeavering.11

Here, building D2 sits atop a spur of land between Yeavering Bell to the south and the river Glen to the north.12 The marshy approaches to the river further accentuate the properties of the spur of land on which building D2 sits.13 Marking the site out as a liminal space between the heights of the Cheviot hills and the depths of the river.

However, this particular example is one of the most explicit in its relation to water. Sites such as Goodmanham in East Yorkshire appear today as very much devoid of proximity to those liminal places where water interacts with the land.14 Yet the site itself lies within the Vale of York not far from the rivers Foss and Ouse.15 However, it is a tenuous connection with the rivers themselves considering their distance from the location.

Although the Vale of York has been a patchwork of small tributaries of both these rivers throughout the history of the landscape.16 Small tributaries that have emerged, diverted, and dried regularly.17 Consequently, it is not possible to factually prove a relationship with a body of water for this site without future archaeological investigation. A statement which also can also unfortunately be applied to the vast majority of known Temple sites across England.

Depicted: Greenstead Church in Essex, an example of the early stave style characteristic of Germanic Heathen temples; Order photo, September 2022.

This lack of archaeological investigation into Temple sites across England further proves itself when considering the physical evidence for the presence of standing posts at Temple sites. Parallels with which are obvious in the Irminsul of the Saxons on the continent as recorded in the Royal Frankish Annals.18 The only excavated comparable evidence for a similar practice is again at the Yeavering Temple site.19 Yet, Harrow Hill in Sussex is a strong contender for a site which more closely adheres to the know elements of the Irminsul on the continent.20

However, until there is further archaeological investigation into this site and others like it then there is little certainty as to how far this commonality extended across other sites in England. Other than a single certain example of Yeavering, a strong contender in Harrow Hill from geophysical surveys done of the site and evidence that there may have been a standing post at the Royal site of Sutton Courtenay.21

Again, the lack of research into the field of early Anglo-Saxon religious structures hinders the certainty with which the standing post can be considered a feature of Temple sites across the wider landscape. However, when it is evident that there is a standing post present then the deposition of animal bones in proximity to the post mark them out as undoubtably religious structures.22

Especially so when compared to the depositional evidence of middens of a similar date the depositions around standing posts appear consistent in the types of bones deposited and the stratification of said depositions across a regular and structured time frame.23 Consequently, it can be noted with some certainty that these ritual depositions were made in accordance with seasonal rites. Depositions in this style also appear within the Temple building at Yeavering, likewise disarticulated.24

Suggesting that the animals to which the bones belonged were ritually slaughtered away from the Temple buildings, which could point to this being part of a feast in which the choice cuts were given to the Gods, then the remains buried as a part of the offering of the animal. Additionally, the consistency of the bones deposited inside the Temple building at Yeavering were found to be overwhelmingly the skulls of oxen (97%) between the ages of 12 to 42 months.25 Indicating again that this was absolutely a deposition of ritual intent.

To conclude, each of these common factors seen across Temple sites in England can be illustrative of what should be kept in mind when considering the construction of new Temple sites for our faith. Despite the evidential lack of investigation which has been undertaken on these sites as new evidence gradually begins to emerge, such as the discovery of the cultic site at Rendlesham last year as of the writing of this, there will surely be a more complete picture of what defines the Anglo-Saxon Temple.

Especially so in terms of what factors were taken into consideration when selecting a site for construction. Despite this, what is evident in the known sites are factors which indicate the land selected for the building of Temples underwent a rigorous selection process to ensure the completed building was fit for purpose. In the same way that it would be improper to wash an item with a dirty cloth, the space used for offering to the Gods must also be made spiritually clean for worship.

II. Bibliography

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Brennan, N and Hamerow, H. (2015) An Anglo-Saxon Great Hall complex at Sutton Courtenay/Drayton, Oxfordshire: A Royal Centre of Early Wessex? Archaeological Journal, 172 (2).

North, R. Eostre the Goddess and the free-standing posts of Yeavering. In: Lacey, ME, (ed) Starcraeft: Watching the Heavens in the Middle Ages. Amterdam University Press: Amsterdam.

Hamerow, H. (2010). Herrenhofe in Anglo-Saxon England. 33, 275-283. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Semple, S. (2010) In the open air. In: Carver, M and Sanmark, A (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited.

According to the Royal Frankish Annals (Anonymus ([790]): chapter 772)

Walker, J. (2010). In the Hall. In Carver, M and Sanmark, A. (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon paganism revisited. Oxbow Books: Oxford.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Brennan, N and Hamerow, H. (2015) An Anglo-Saxon Great Hall complex at Sutton Courtenay/Drayton, Oxfordshire: A Royal Centre of Early Wessex? Archaeological Journal, 172 (2).

Walker, J. (2010). In the Hall. In Carver, M and Sanmark, A. (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon paganism revisited. Oxbow Books: Oxford.

North, R. Eostre the Goddess and the free-standing posts of Yeavering. In: Lacey, ME, (ed) Starcraeft: Watching the Heavens in the Middle Ages. Amterdam University Press: Amsterdam.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Walker, J. (2010). In the Hall. In Carver, M and Sanmark, A. (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon paganism revisited. Oxbow Books: Oxford.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Hamerow, H. (2010). Herrenhofe in Anglo-Saxon England. 33, 275-283. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Hamerow, H. (2010). Herrenhofe in Anglo-Saxon England. 33, 275-283. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Semple, S. (2010) In the open air. In: Carver, M and Sanmark, A (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Semple, S. (2007) Defining the OE Hearg: A preliminary and topographical examination of Hearg place names and their Hinterlands. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing LTD.

Hamerow, H. (2010). Herrenhofe in Anglo-Saxon England. 33, 275-283. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Hamerow, H. (2010). Herrenhofe in Anglo-Saxon England. 33, 275-283. Oxford University Press: Oxford.

Semple, S. (2007) Defining the OE Hearg: A preliminary and topographical examination of Hearg place names and their Hinterlands. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing LTD.

According to the Royal Frankish Annals (Anonymus ([790]): chapter 772)

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Semple, S. (2010) In the open air. In: Carver, M and Sanmark, A (ed) Signals of Belief in Early England. Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited.

Brennan, N and Hamerow, H. (2015) An Anglo-Saxon Great Hall complex at Sutton Courtenay/Drayton, Oxfordshire: A Royal Centre of Early Wessex? Archaeological Journal, 172 (2).

North, R. Eostre the Goddess and the free-standing posts of Yeavering. In: Lacey, ME, (ed) Starcraeft: Watching the Heavens in the Middle Ages. Amterdam University Press: Amsterdam.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.

Hope-Taylor, B. (1977) Yeavering. An Anglo-British centre of early Northumbria. English Heritage: Swindon.